Which Counties Had More Votes Than Registered Voters In 2018

If early voting trends are whatever indication, a tape number of Americans could vote in the 2020 presidential ballot. Equally of this writing, more than than 100 million early votes have been bandage by mail or in person – more two-thirds of the full number of votes cast in 2016.

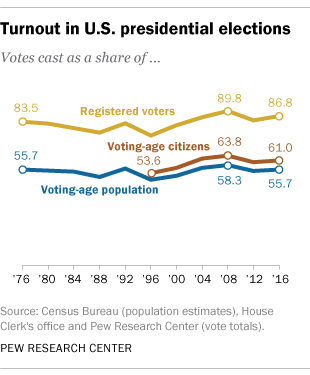

We won't have anything like a definitive assessment of 2020 turnout rates for some time after Nov. 3. But in the 2016 presidential election, almost 56% of the U.S. voting-age population cast a ballot. That represented a slight uptick from 2012 simply was lower than in the record twelvemonth of 2008, when turnout topped 58% of the voting-historic period population.

So how does voter turnout in the United States compare with turnout in other countries? That depends very much on which state you're looking at and which measuring stick y'all employ.

Political scientists often ascertain turnout as votes cast divided by the number of eligible voters. But because eligible-voter estimates are not readily available for many countries, nosotros're basing our cantankerous-national turnout comparisons on estimates of voting-age population (or VAP), which are more readily available, as well as on registered voters. (Read "How nosotros did this" for details.)

Comparing U.S. national ballot turnout rates with rates in other countries can yield different results, depending on how turnout is calculated. Political scientists oftentimes define turnout as votes cast divided past the estimated number of eligible voters. But eligible-voter estimates are difficult or impossible to find for many nations. So to compare turnout calculations internationally, we're using two dissimilar denominators: total registered voters and estimated voting-age populations, or VAP, considering they're readily available for most countries.

We calculated turnout rates for the well-nigh recent national election in each state, except in cases where that ballot was for a largely ceremonial position or for European Parliament members (turnout is often substantially lower in such elections). Voting-age population turnout is derived from estimates of each country'south VAP by the International Institute for Commonwealth and Electoral Assist. Registered-voter turnout is derived from each land'southward reported registration data. Because of methodological differences, in some countries Thought's VAP estimates are lower than the reported number of registered voters.

In addition to information from Idea, data is likewise drawn from the U.South. Census Bureau, the Function of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, and individual nations' statistical and election authorities.

Overall, 245.5 million Americans were ages xviii and older in November 2016, nearly 157.6 million of whom reported being registered to vote, according to Census Bureau estimates. Just over 137.5 million people told the census they voted that year, somewhat higher than the bodily number of votes tallied – near 136.8 1000000, co-ordinate to figures compiled by the Part of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives (which include more than 170,000 blank, spoiled or otherwise cipher ballots). That sort of overstatement has long been noted by researchers; the comparisons and charts in this assay use the Business firm Clerk's effigy, along with data from the International Institute for Democracy and Balloter Assistance and individual nations' statistical and elections authorities.

The 55.7% VAP turnout in 2016 puts the U.S. backside most of its peers in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, most of whose members are highly adult democratic states. Looking at the most recent nationwide election in each OECD nation, the U.S. places 30th out of 35 nations for which data is available.

The highest turnout rates among OECD nations were in Turkey (89% of voting-age population), Sweden (82.1%), Australia (fourscore.8%), Belgium (77.9%) and South Korea (77.9%). Switzerland consistently has the lowest turnout in the OECD: In 2019 federal elections, barely 36% of the Swiss voting-historic period population voted.

Ane cistron backside the consistently high turnout rates in Commonwealth of australia and Belgium may exist that they are amidst the 21 nations around the world, including six in the OECD, with some class of compulsory voting. 1 canton in Switzerland has compulsory voting also.

While compulsory-voting laws aren't ever strictly enforced, their presence or absence can have dramatic furnishings on turnout. In Chile, for example, turnout plunged after the state moved from compulsory to voluntary voting in 2012 and began automatically putting all eligible citizens on the voter rolls. Fifty-fifty though substantially all voting-age citizens were registered to vote in Chile's 2013 elections, turnout in the presidential race plunged to 42%, versus 87% in 2010 when the compulsory-voting law was still in place. (Turnout rebounded slightly in the 2017 presidential election, to 49% of registered voters.)

Chile's situation points to even so another complicating factor when comparison turnout rates across countries: the distinction between who's eligible to vote and who'due south really registered to do so. In many countries, the national government takes the lead in getting people's names on the rolls – whether by registering them automatically in one case they become eligible (every bit in, for example, Sweden or Germany) or by aggressively seeking out and registering eligible voters (as in the UK and Australia). As a result, turnout looks pretty similar regardless of whether you're looking at voting-age population or registered voters.

In the U.South., by contrast, registration is decentralized and mainly an individual responsibleness. And registered voters stand for a much smaller share of potential voters in the U.Southward. than in many other countries. Only about 64% of the U.S. voting-age population (and 70% of voting-age citizens) was registered in 2016, according to the Census Bureau. The U.S. rate is much lower than many other OECD countries: For example, the share of the voting-age population that is registered to vote is 92% in the Great britain (2019), 93% in Canada (2019), 94% in Sweden (2018) and 99% in Slovakia (2020). Luxembourg also has a low rate (54%), although it represents something of a special case because virtually half of the tiny state'south population is foreign born.

As a upshot, turnout comparisons based only on registered voters may non be very meaningful. For example, U.South. turnout in 2016 was 86.8% of registered voters, fifth-highest among OECD countries and second-highest amid those without compulsory voting. But registered voters in the U.S. are much more of a self-selected grouping, already more than likely to vote because they took the trouble to register themselves.

There are even more ways to summate turnout. Michael McDonald, a political scientist at the University of Florida who runs the The states Ballot Project, estimates turnout every bit a share of the "voting-eligible population" by subtracting noncitizens and ineligible felons from the voting-historic period population and adding eligible overseas voters. Using those calculations, U.S. turnout improves somewhat, to 60.1% of the 2016 voting-eligible population. Nonetheless, McDonald doesn't calculate comparable estimates for other countries.

No affair how they're measured, U.Due south. turnout rates have been fairly consistent over the by several decades, despite some election-to-election variation. Since 1976, voting-historic period turnout has remained within an 8.5 percentage point range – from just under l% in 1996, when Bill Clinton was reelected, to just over 58% in 2008, when Barack Obama won the White House. Notwithstanding, turnout varies considerably among different racial, indigenous and age groups.

In several other OECD countries, turnout has drifted lower in recent decades. Hellenic republic has a compulsory-voting constabulary on the books, though it's not enforced; turnout there in parliamentary elections fell from 89% in 2000 to 63.v% last yr. In Norway's most contempo parliamentary elections, 2017, 70.half-dozen% of the voting-historic period population cast ballots – the everyman turnout rate in at least 4 decades. And in Slovenia, a flare-up of enthusiasm followed the country'south independence from Yugoslavia in 1992, when 85% of the voting-historic period population cast ballots – but turnout has fallen virtually 31 percentage points in two-and-a-half decades of republic, sinking to 54.6% in 2018.

On the other mitt, turnout in recent elections has bumped upwards in several OECD countries. Canadian turnout in the two virtually recent parliamentary elections (2015 and 2019) topped 62%, the highest rate since 1993. In Slovakia's legislative elections this past Feb, nearly two-thirds (65.4%) of the voting-age population cast ballots, up from 59.4% in 2016. And in Hungary's 2018 parliamentary elections, well-nigh 72% of the voting-age population voted, up from 63.3% in 2014.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 6, 2015.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout/

Posted by: espinosalasuall.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Counties Had More Votes Than Registered Voters In 2018"

Post a Comment